Postcards from the Middle East by Chris Naylor: 5. Conservation conversations

2000 Jabal Rihan, Lebanon

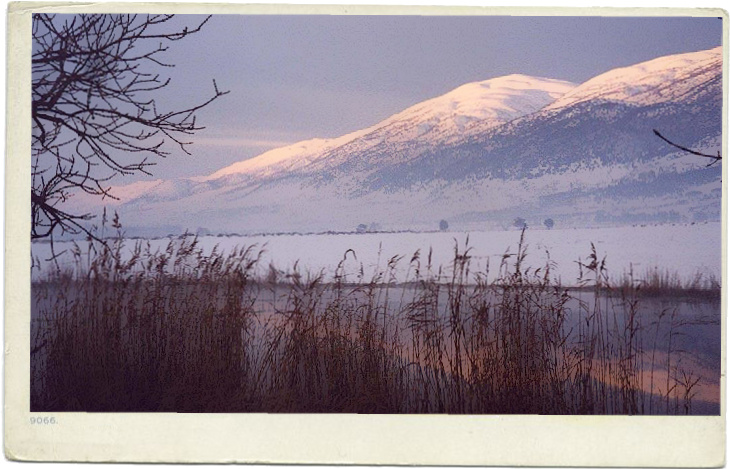

The Aammiq wetland in winter, looking south along the Mount Lebanon range

I was in a wood with Abouna, a Melkite priest who I had met in Beirut.…

Abouna had gathered a flock of scientists to make an inventory of the wood so that he could make a presentation to the authorities; a catalogue of riches that had survived, against the odds, in this precious fragment and artefact of war. Most of the trees in the region had long been cleared, but the current threat to the habitat was no longer conflict but an explosion in development; a building boom. If the experience of Beirut was to be repeated, it would be in the post-war years that most of the natural habitat would be lost. In the dash for growth, regulations were often inadequate or ignored, and natural areas, slated for urban sprawl, poorly understood and little studied. With concrete being the new habitat, wildlife literally went to the wall.

Abouna recognized that the population returning after the end of the Israeli occupation needed houses, schools, shops, and roads. But he also realized that they had been left a gift from previous generations. It had been locked in storage and was now unexpectedly precious and rare. With planning and care the communities could grow and preserve their natural heritage. The village could keep its backcloth of oak and pistachio, sycamore and myrtle, while housing its returning refugees and educating its children.

However, bringing a community to the point where it is prepared to limit its ambition, to put boundaries on its development, requires a long conversation. Our bird monitoring was providing some of the context for the discussion, but Abouna also took lessons from the community involvement at Aammiq. Increasingly we found this to be the case. Yes, we were often asked (and even occasionally paid) to study the wildlife of areas in need of conservation, to help assemble the scientific case for their protection, but even more often groups came to Aammiq to see how a community dialogues and decides to restrain itself from more and more consumption of land, resources, and wildlife to the benefit of all and for a heritage to be passed on to future generations.

One of the great things about being involved in a community dialogue is who you meet and who you enlist to help to bring the information to inform the decisions. A Rocha brought three things to the conversation at Aammiq.

Firstly, we recruited a stream of experts who could study the ecosystem of the wetland and answer such questions as: ‘What animals and plants live there? What do they need to thrive? How does the wetland work? Which parts are the most important for flood control, water retention and so on?’

Secondly, we helped the community experience the majesty and delight of creation. This happened in two places – certainly in the wetland with enthusiastic children catching tadpoles, overawed adults looking at the iridescent plumage of a kingfisher, and farmers learning about the micro climate the wetland created, benefiting their crops. But it also happened in churches where, with the congregations, we unpacked the Bible’s message to look after, to steward, the creation. A favourite verse of mine to get discussion started was perhaps the best-known verse in the Bible: ‘God so loved the [cosmos] that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life.’ Just by using the original term from the Greek, “cosmos”, rather than “world” immediately set preconceptions astir and got people to listen and talk.

Thirdly, we worked with the estate and community to implement the habitat protection and restoration project, overseeing ditches closed, pools created, dams constructed, trees planted, and a hundred other things that make up a community conservation project.

This is also a global conversation. The landowners, farmers, scientists, villagers, hikers, artists, and hunters of Aammiq are actors in microcosm. All over the world, communities are engaged in the same discussion. Because these issues cannot be confined to communal, local, national, or even regional borders, this is a truly global dialogue.

Unfortunately with global dialogues, rather than local ones, there is often a disconnect; those who are responsible for the greatest consumption are not the ones most aware of the destruction. So we can have our hardwood furniture without seeing the loss of Indonesia’s forests, and the communities of the Maldives may lose their homes to sea level rise without having contributed their fair share to the atmospheric carbon. Not so at the local level.

This is the fifth of six excerpts from Postcards from the Middle East by Chris Naylor. Published by Lion Hudson in March 2015, it can be ordered from its page on the Lion Hudson website

We are happy for our blogs to be used by third parties on condition that the author is cited and A Rocha International, arocha.org, is credited as the original source. We would be grateful if you could let us know if you have used our material, by emailing [email protected].