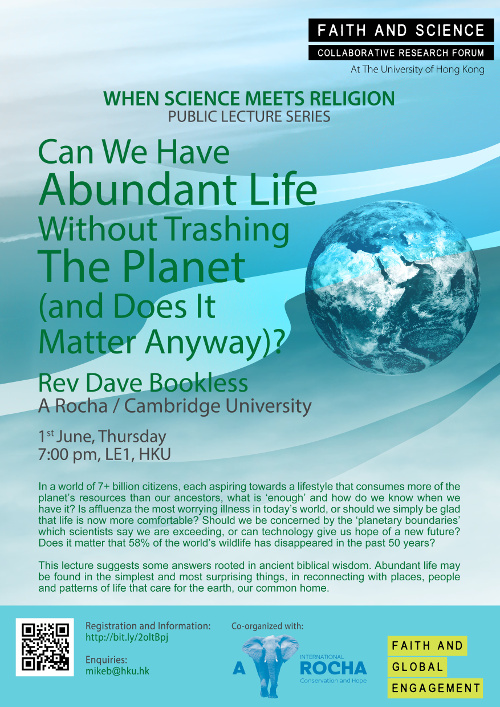

Can we have abundant life without trashing the planet?

Based on a talk given at Hong Kong University, 1st June 2017

What do we mean by ‘abundant life’? Both Western and Eastern cultures tend to value ‘success’ in terms of prosperity, wealth, health, long-life and security, and increasingly in the 21st century also freedom and mobility (autonomy). Yet we live with the paradox that, particularly with a fast-growing global population, the pursuit of these goals is putting increasing pressure on the natural environment, and also on social and economic stability. The conventional three pillars of sustainable development – the economic, social and ecological – are all under great strain. Economic systems built on an unending supply of cheap fossil fuels and of demand for disposable consumer products are colliding with the planetary boundaries within which we need to stay for long-term sustainability.

What do we mean by ‘abundant life’? Both Western and Eastern cultures tend to value ‘success’ in terms of prosperity, wealth, health, long-life and security, and increasingly in the 21st century also freedom and mobility (autonomy). Yet we live with the paradox that, particularly with a fast-growing global population, the pursuit of these goals is putting increasing pressure on the natural environment, and also on social and economic stability. The conventional three pillars of sustainable development – the economic, social and ecological – are all under great strain. Economic systems built on an unending supply of cheap fossil fuels and of demand for disposable consumer products are colliding with the planetary boundaries within which we need to stay for long-term sustainability.

Moreover, there is increasing evidence that material wealth beyond a certain level creates psychological and social stresses which are destabilizing to individuals and whole societies. We clearly need economic development to raise the world’s poorest to a level where all basic needs are met, but ‘growth for growth’s sake’ needs to be questioned. What is growth for? Can economies be reconstituted in a way that is more circular or even restorative in their use of natural resources? Can economics recognize that the environment is never an externality?

These questions beg a different approach to the question of ‘abundant life’. The environmentalist Jonathon Porritt has written, ‘There are few sources of authority (let alone wisdom) in addressing these challenges that are not derived from religious or spiritual sources’ [1]. When King Solomon was offered any gift he wanted from God, he chose not money, possessions, health, security or power … but wisdom (2 Chr 1:7–12). Wisdom, as a way of understanding reality, is different from scientific knowledge and rational analysis. It is a way of knowing the world relationally. In its biblical definition it consists primarily in ‘knowing our place’ in the world: knowing ourselves in relationship to God, other people, and nature.

Truly abundant life is not found in abundance of material possessions but in the quality of our relationships. Jesus said, ‘Watch out! Be on your guard against all kinds of greed; life does not consist in an abundance of possessions’ (Luke 12:15). We need to foster key values and virtues in our pursuit of a truly abundant life, and ensure these transform all three key dimensions of our relationships – with God, others and nature. These also need to be integrated into our educational system – our formation of hearts and minds, and into our political and economic life as well. In terms of biblically-based values and virtues that may be acceptable across cultures and ideologies I would suggest we need to foster:

- Interdependence: we are all in this together – all people equally made in God’s image, and nonhuman creatures towards whom we are called to reflect God’s creative and loving image. We need each other and depend on each other. The virtue of wonder helps foster our sense of interdependence – the realization that all things are connected and life is a precious gift.

- Relationship: an orientation towards others – not seeking satisfaction in self-fulfilment but in seeing others – and nature – thrive. To be truly human is to be ‘eccentric’ in the sense of being centred not on ourselves but on the ‘other’ – finding our joy in the flourishing of other people and other creatures. The virtue of humility recognizes that we are fundamentally related to the ‘humus’ – the earth from which all things are created, and that leadership is servant-hearted.

- Localism: rootedness and belonging in the places God plants us; wisdom values knowing our local place because only then do we really belong somewhere. Studies show that individuals and businesses become more environmentally damaging once they become remote from the places their raw materials, products and lives impact. Just as Solomon knew the birds, animals and plants of his Kingdom (1 Ki 4:33) so we should learn our local ecology and share that knowledge. Restraint is a key ecological virtue that stems from seeing the impacts our votes, our purchasing, our lives have on fellow people and fellow creatures, and seeking to minimize our harmful impact.

- Holism: seeing the big picture; recognizing our footprint and impact, and taking account of the needs of the whole planetary system. The Christian gospel must never be reduced to individual salvation or ‘spiritual values’. It is God’s plan for the renewal and redemption of the whole universe in Christ. The core Christian virtues of faith, hope and love (1 Co 13:13) are not fuzzy feelings for church services, but practical attitudes to take to our work-places, our homes, our shopping and all our interactions with God’s good creation. God’s faith, hope and love extend to his plans for renewing all things in Christ – and so must ours.

[1] SDC/WWF-UK (2005). Sustainable Development and UK Faith Groups: Two Sides of the Same Coin? London, Sustainable Development Commission.

We are happy for our blogs to be used by third parties on condition that the author is cited and A Rocha International, arocha.org, is credited as the original source. We would be grateful if you could let us know if you have used our material, by emailing [email protected].

[…] 2017, I spoke in Hong Kong on: ‘Can we have abundant life without trashing the planet?’ I began with popular definitions of human flourishing: Health, Wealth, Possessions, Security, […]